Average Cost of Flood Insurance

The average cost of flood insurance from the NFIP is $985 per year or $82 per month.

Find Cheap Homeowners Insurance Quotes in Your Area

While the average cost of flood insurance in the U.S. is $985 per year or $82 per month, your own rates may vary. The average premium you'll pay for flood insurance depends on factors such as your state, how much coverage you need and your proximity to water.

Average cost of flood insurance by state

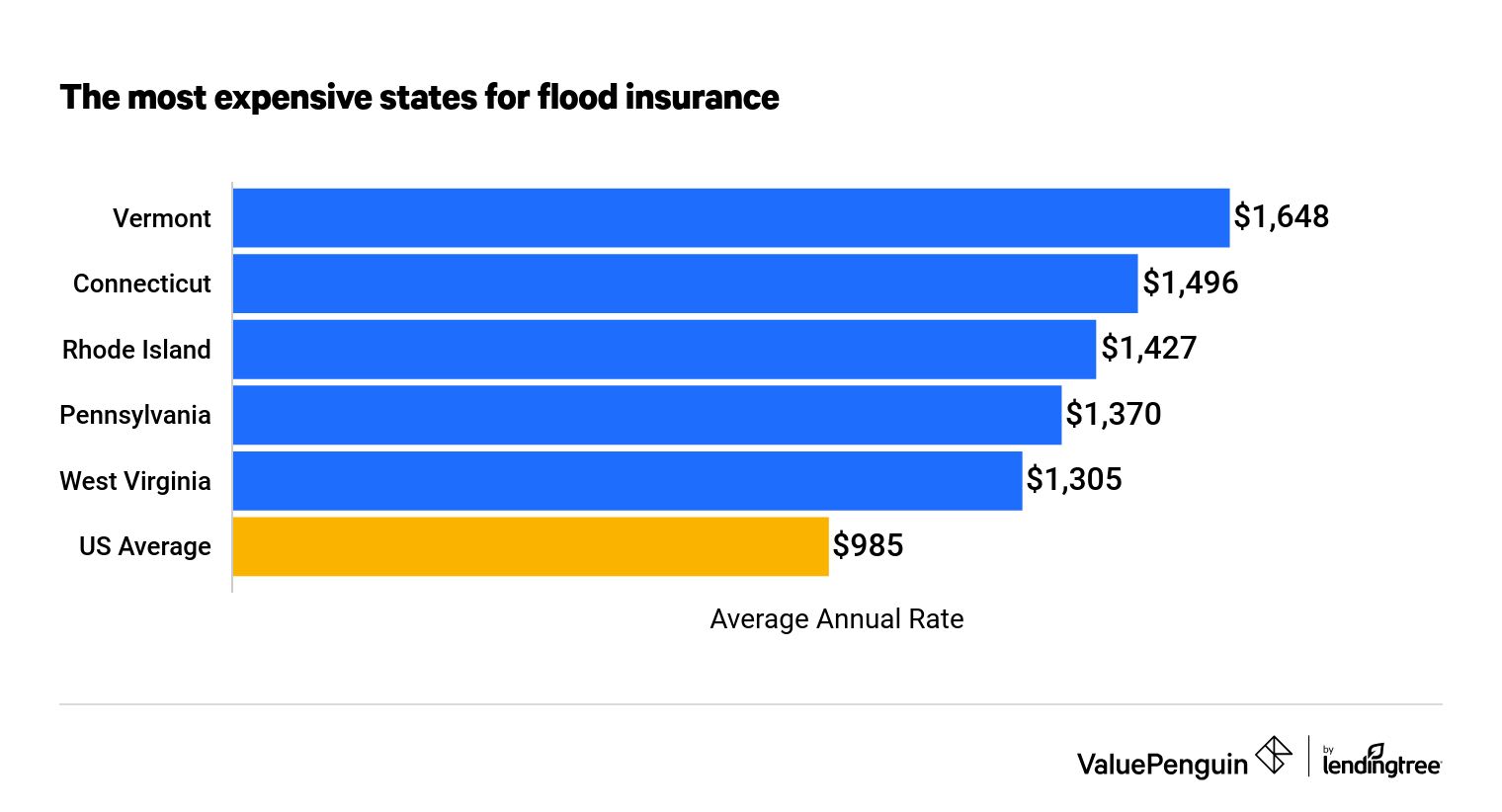

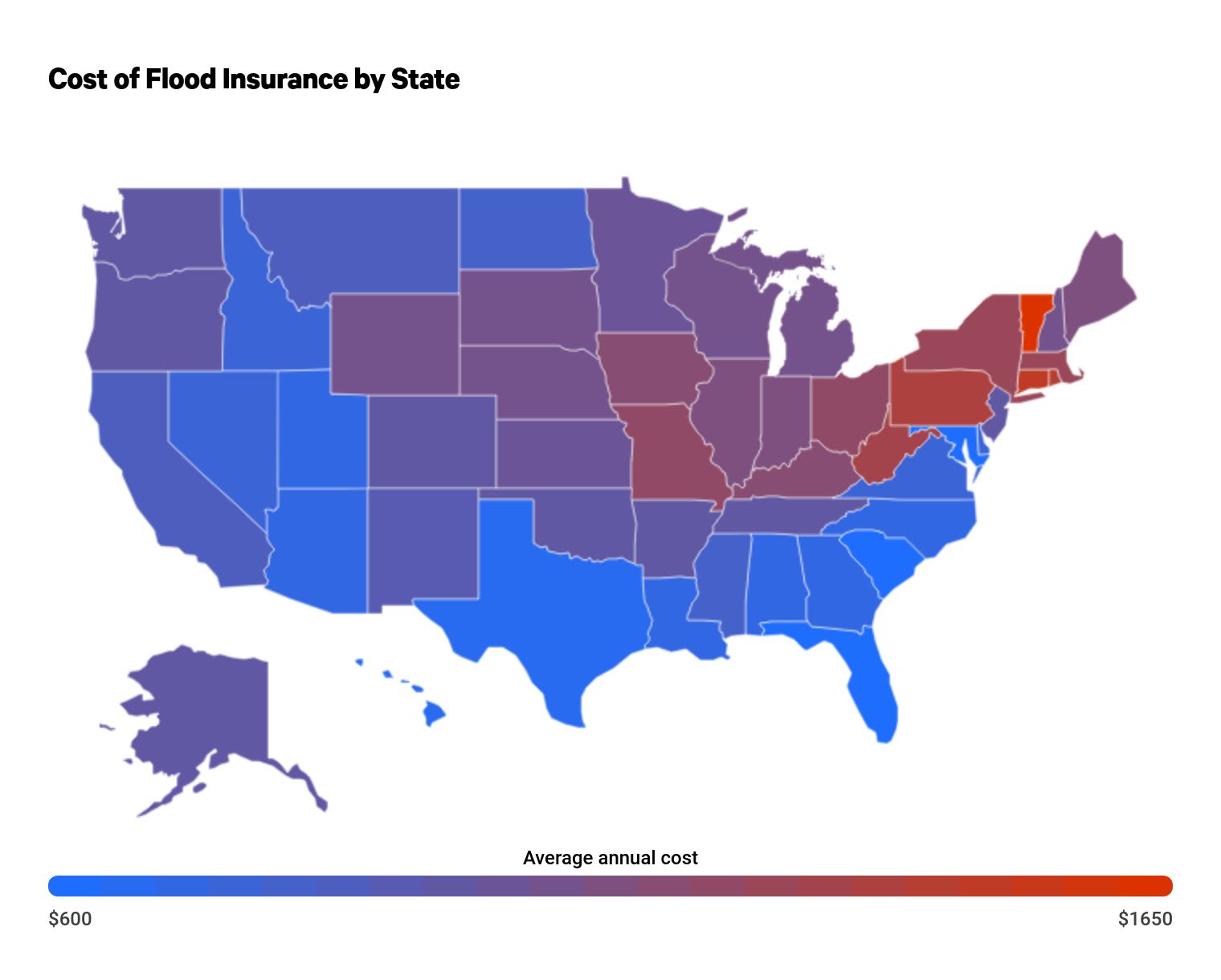

Both homeowners and renters can get flood insurance coverage from the NFIP, which is managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The average annual premiums for flood insurance vary by up to $1,035 between states.

Compare how much the average homeowner in each state pays for NFIP flood insurance. Differences in location and coverage amounts can lead to major variations in cost.

Find Cheap Homeowners Insurance Quotes in Your Area

The average cost of flood insurance appears to be cheaper in the South but quite high in the Northeast and Midwest. However, prices can be different within the same state depending on whether you look for NFIP policies or policies from private flood insurers.

Average cost of flood insurance by state

State | Average cost per year | Difference from U.S. average |

|---|---|---|

| Vermont | $1,648 | 67% |

| Connecticut | $1,496 | 52% |

| Rhode Island | $1,427 | 45% |

| Pennsylvania | $1,370 | 39% |

| West Virginia | $1,305 | 32% |

| Massachusetts | $1,298 | 32% |

| New York | $1,266 | 29% |

| Missouri | $1,228 | 25% |

| Ohio | $1,211 | 23% |

| Iowa | $1,199 | 22% |

| Kentucky | $1,150 | 17% |

| Indiana | $1,147 | 16% |

Data calculated by dividing each state's total written premiums by number of active flood insurance policies

States with the highest average flood insurance costs

The three most expensive states for NFIP flood insurance premiums, Vermont, Connecticut and Rhode Island, are located in New England. Nearby Pennsylvania ranks fourth.

States with the lowest average flood insurance costs

The three flood-prone states of Florida, Maryland and South Carolina are among the more affordable places to find NFIP coverage. Florida is the cheapest place to get flood insurance, with an average rate of $613 per year. Costs by state depend on the amount of flood coverage homeowners receive on their policies.

Cost of private flood insurance

Private flood insurance has recently grown in popularity as an alternative to the NFIP, but not all states have access to a private flood insurance company. One of the largest private insurers, The Flood Insurance Agency (TFIA), operates in 48 states and is currently the only company offering online quotes.

Rates aren't affected by state borders so much as by your distance from the water's edge. Private flood insurance pricing is heavily influenced by FEMA's flood maps. Regardless, the agency's mapping accuracy has drawn criticism from both insurers and homeowners.

What does flood insurance cover?

Similar to homeowners insurance, private flood insurance provides coverage for both your building property and personal property. In contrast, NFIP flood insurance requires you to buy these two coverages separately.

Building property coverage will reimburse you for flood damage to your home’s structure, up to your policy limit. This includes the foundation, electrical and plumbing systems, HVAC systems and appliances, such as refrigerators and stoves.

Personal property coverage will pay for flood damage to your personal belongings. This includes personal belongings ranging from furniture and portable appliances to clothes and food. Individual sublimits will often restrict coverage for valuable items like artwork. For an NFIP policy, these sublimits are set at $2,500.

NFIP policies are limited in their coverage. Private flood insurers can offer higher limits, making them preferable for homeowners with high-value assets.

Do I need flood insurance?

If you have a mortgage for a property in an area that's particularly vulnerable to flooding, your lender will probably require you to buy additional flood-specific coverage, as mandated by federal regulations.

You should seriously consider getting flood insurance if you live in a high-risk flood zone. According to FEMA, floods are the most common natural disaster in the country, and they're one of the most expensive if you have to make a claim. You can find out if you live in a high-risk flood zone by looking up your address on the FEMA Flood Map Service Center.

Even if you don't live in a high-risk zone, you should consider purchasing flood insurance. No property has zero risk of flooding: In fact, approximately 25% of all flood insurance claims are made in low-to-moderate flood risk areas. In these areas, homeowners qualify for FEMA's preferred risk policy, available at cheaper rates as low as $129 per year for dwelling and contents coverage.

Are homeowners covered for flood damage?

Many homeowners are unaware that most standard home insurance policies do not cover flood damage.

Lenders usually only require borrowers to buy flood insurance if their homes are in a high-risk area for flooding. This means flood insurance policies are far less widespread than home insurance, which is required on virtually every mortgage.

Over 90% of owner-occupied homes have homeowners insurance in the U.S. Only 2.6% have an NFIP flood insurance policy.

The ratio of flood insurance coverage varies by state. Residents in coastal states tend to buy flood insurance policies in much higher numbers than those in inland areas. This is reflected in the states with the highest and lowest ratios of active flood insurance:

Most-insured states | Least-insured states |

|---|---|

| 1. Louisiana (24.4%) | 51. Minnesota (0.3%) |

| 2. Florida (17.7%) | 50. Utah (0.3%) |

| 3. Hawaii (11.0%) | 49. Michigan(0.4%) |

| 4. South Carolina (8.8%) | 48. Wisconsin (0.4%) |

| 5. Texas (7.0%) | 47. Ohio (0.5%) |

Homeowners with flood insurance is an estimate based on the ratio of NFIP policies in force (FEMA) to owner-occupied housing units (U.S. Census Bureau). Analysis excludes private flood insurance policies. Analysis includes the District of Columbia.

State | Homes | Active policies | Insured homes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louisiana | 2,089,777 | 509,020 | 24.40% |

| Florida | 9,673,682 | 1,714,008 | 17.70% |

| Hawaii | 550,273 | 60,529 | 11.00% |

| South Carolina | 2,351,286 | 206,573 | 8.80% |

| Texas | 11,283,353 | 786,051 | 7.00% |

| Delaware | 443,781 | 263,86 | 5.90% |

| New Jersey | 3,641,812 | 210,483 | 5.80% |

| Mississippi | 1,339,021 | 60,997 | 4.60% |

| North Carolina | 4,747,943 | 139,127 | 2.90% |

| Virginia | 3,562,143 | 100,739 | 2.80% |

| Maryland | 2,470,316 | 64,563 | 2.60% |

| Rhode Island | 470,168 | 11,254 | 2.40% |

Homeowners with flood insurance is an estimate based on the ratio of NFIP policies in force (FEMA) to owner-occupied housing units (U.S. Census Bureau). Analysis excludes private flood insurance policies.

Expert insights to help you make smarter financial decisions

ValuePenguin has curated an exclusive panel of professionals, spanning various areas of expertise, to help dissect difficult subjects and empower you to make smarter financial decisions.

- With sea levels rising, do you see the risk of flooding becoming a more prominent worry for homeowners in the future?

- Do you believe there will be a point when high-tide flooding transitions from a regional issue to a nationwide problem?

- It’s been featured in the news recently that NASA suspects the combination of climate change and the moon’s natural "wobble" could result in record flooding in the 2030s. Is this inference something that people should start planning for now?

- What are some measures people can take to effectively mitigate the effects of flooding today?

- Chris Karmosky

- Assistant professor of meteorology and climatology

- Read answer

Chris Karmosky

Assistant professor of meteorology and climatology, SUNY Oneonta

With sea levels rising, do you see the risk of flooding becoming a more prominent worry for homeowners in the future?

In short — yes. The recent (2021) report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change indicates that flood events will become more frequent and more intense because of climate change. Not only will sea levels be rising, but more frequent and more intense storm systems pile on top of that. So if the same strength storm hits an area that was hit years ago, now the flooding is worse because of sea-level rise. But on top of that, the warming climate means that storms are likely to be even stronger, which also means that flooding will be worse.

This "one-two punch" of stronger storms and higher sea levels is concerning. And while we often think about flooding in coastal regions, inland river and stream flooding can also become more of a problem as the climate changes.

Do you believe there will be a point when high-tide flooding transitions from a regional issue to a nationwide problem?

While high-tide flooding is projected to become worse due to sea-level rise, not all coastlines will be affected by this phenomenon. Coastlines with a steep incline into the ocean, such as on the west coast of the U.S., will experience far less inundation (flooding) than the more level east coast. The East Coast region contains the areas that are already seeing the most significant high-tide flooding, particularly the Mid-Atlantic and the Southeast.

The geometry of the coastline, prevailing wind direction and underlying geology also affect a region’s vulnerability to high-tide flooding. So while more frequent and more intense high-tide flooding events are expected in the coming decades, and some places will experience high-tide flooding that didn’t before, this will remain a regional issue, with perhaps some expansion of the regions affected.

It’s been featured in the news recently that NASA suspects the combination of climate change and the moon’s natural "wobble" could result in record flooding in the 2030s. Is this inference something that people should start planning for now?

It’s always prudent to plan ahead for flooding events. I’m far more concerned not just about the moon’s "wobble" but about the potential for multiple factors to enhance flooding at the same time — specifically sea-level rise added to flooding from existing and now stronger storms. Variations in the lunar cycle have masked some sea-level rise to this point but will begin to enhance sea-level rise in the coming decades.

Should people plan now? Weather forecast models have become so much better even in just the last decade and can forecast flood events several days in advance with impressive results. And while this might be enough time to evacuate from a hurricane, or deploy temporary sandbags, it’s not always enough time to adequately protect waterfront and water-adjacent property. Property improvements can take months or even years to plan and carry out. And of course, local, state and federal government flood mitigation efforts can take much longer. Therefore, it’s imperative that planning for things to get worse in the future begins now.

What are some measures people can take to effectively mitigate the effects of flooding today?

As I am someone with a background in geography, to me this is a question of scale. There are certain smaller-scale things that homeowners can do themselves to mitigate flooding — shoreline protection measures, ensuring effective drainage with proper grading of the property and regularly clearing storm drains of debris. That last one is an often-overlooked measure that can greatly help with flooding, especially in autumn months when fallen leaves regularly clog drains.

Then there are larger-scale issues that go beyond what any single homeowner can take on. This includes the preservation of wetlands (which serve as a natural flooding buffer), reducing the number of paved surfaces and maintenance of levees and storm walls. Proper local and regional planning can provide protection for not just one person or family but for the whole community.

Methodology

For our analysis of U.S. flood insurance costs, we referred to the most recently available rate data and state-specific breakdowns from the National Flood Insurance Program. The percentage of homeowners with flood insurance was based on the ratio of NFIP policies in force to the number of owner-occupied housing units, which came from the U.S. Census Bureau.